Leigh Star’s claim that, “Infrastructure becomes visible upon breakdown” strikes me as incredibly related to translation whenever I hear it (Star 2010: 611). Yes, translation, particularly that of games, is marked by its invisibility. One recent poster to the International Game Developers Association Localization Special Interest Group message board wrote “you either get no qualitative feedback when a job is done well or you get negative feedback” (IGDA LocSIG Sep 24, 2012). A second states “As for localization effectiveness, I think it’s similar to good film soundtracks: if you don’t notice it, it’s great” (IGDA LocSIG Sep 24, 2012). For both of these localization specialists their experience is that a good translation is unremarked upon and invisible.

Such a beginning leads me to two general theories that Star has worked on. The first is that of boundary objects (Star and Griesemer 1989), and the second is visibility and/of work (Star and Strauss 1999).

While I tend to think of translation as an interface that is actively manipulated by translators in order to alter a text so that it works between people and cultures, it would be not too much of a stretch to think about the practice of localization as a “boundary object” (Star and Griesemer 1989). Everybody — programers, translators and players included — works and interacts on the same text even as it is manipulated and used differently. The problem I find with the boundary object methodology (metaphor?) is highlighted in Star’s 2010 reiteration of her and Griesemer’s three part definition. She begins be noting that, “The object… resides between social worlds (or communities of practice) where it is ill structured” (Star 2010: 604). Games, as locally created texts (never universal despite claims to the contrary) are necessarily between worlds/communities of practice be they national or linguistic. So far, so good.

Star continues by saying, “When necessary, the object is worked on by local groups who maintain its vaguer identity as a common object, while making it more specific, more tailored to local use within a social world, and therefore useful for work that is NOT interdisciplinary” (Star 2010: 604-5). Here is where things get very similar, but at the same time very off when thinking about game translation. The idea that “local groups” work on a game doesn’t hold as it is a third party group, the translator/localizer, and not the participant/player. Although the best localizers are also players, they are forcibly removed from their sociality through NDA restrictions of secrecy. There is a break between the social community: essentially, while under translation there is no community, particularly for freelancers who are forbidden to talk to others. However, somebody works to tailor a game to local use — the whole definition of localization is exactly such: to render local for consumption. Finally, we have an incredibly interesting bit: the result of such boundary work is that the object becomes “useful for work that is NOT interdisciplinary.” If we’re going to continue with the localization practice of games, then local play of games is NOT global. Said another way: translators alter the text so that you do not have to deal with the messiness of inter[action] with an Other.

Finally, Star (and Griesemer)’s third definitional clause is that “Groups that are cooperating without consensus tack back-and-forth between both forms of the object” (Star 2010: 605). And here is where the relationship between localization and boundary objects seems to fall apart. The nature of games as global texts is that they are simultaneously consumed in different forms by people in different locations as the same text. Furthermore, access to “both forms of the object” (eg: both translations/localizations) is generally rendered impossible (PS2), expensive (DS), or difficult (iPhone). Granted, sometimes and in particular places, these different versions are rendered visible. The most obvious example of this exists with European developers and for European versions. Because of the reality of living between languages, a typically visible European method of coding different versions is often more structural (you choose the language when you start the game) than infrastructural (matches system language; only one language per disk). In this European situation the translation is still a boundary object as it is visible. However, in both the current trend and (almost) all games between Japan and the United States there is no cooperation, consensus, or back-and-forth. Is this a good or bad “standardization” according to Star? That, I’m not quite sure of, but following with the lack of inter[action], my own feeling is that it is ethically problematic.

Yes, certain aspects of the boundary object met[thod/aphor] resonate with a study of game translation. However, there are simply too many nitty gritty details that don’t work, particularly the invisibility of the NDA. And here is where I can transition from the front-running popular theory, to the secondary one that seems to be more viable given the translation/localization context: visibility and work.

While unrelated to her work on boundary objects other than through the conceptualization of infrastructure and its invisibility, Star’s writings on work (in)visibility is quite helpful in understanding game localization. Star and Strauss (1999) argue that there are two forms along which work invisibility can be seen, the invisible worker and the invisible work. The first is painfully exemplified in Rollins’ (1985) work on African-American housekeepers where the workers are reduced to the status of invisibility even while their work is valued. A less racially painful, but similar example from early video game history is how programmers’ names (and work) were struck from the games they created. In an attempt to keep programmers from gaining status and therefore the ability to require greater pay, publishers kept programmers anonymous and games were published with only the publishing company’s name. One of the first programmers to gain visibility was Warren Robinett, who inserted his own name into Adventure, the Atari game he was programming. While (many) programmers have since gained authorial/visible status and are now a part of ‘history,’ other workers remain invisible. Translators are my key example, as their work is visible to publishers, but their names are not to be granted visibility. According to one interviewee, translation is a ‘service economy’ — just like housekeeping. Because of translation’s ‘service’ status, the translators themselves become invisible ‘service workers.’ The second form of invisibility is when the work becomes invisible due to its taken for granted status. Because it is taken for granted it begins to be invisible. Star points toward parents, secretaries and call-services, but her primary example is nurses. She notes that, “If one looked, one could literally see the work being done – but the taken for granted status means that it is functionally invisible” (1999: 20). This sort of work is absolutely necessary for standard practices to continue, but its importance and prevalence is generally overlooked. For global media this is translation to a T: media is global thanks to translation, but nobody ever bothers to think about it as it is part of the infrastructure.

So, translation fits with both types of invisibility. However, like with Suchman’s (1995) discussion about rendering visible, translators’ desire to be visible is not a simple issue. Writings on translation theory have discussed the issue of trust, but between the speaker/writer and the translator, and the speaker/writer and audience (as mediated by the translator). Located in a double bind, the translator is ethically required to translate faithfully the words and intentions of the speaker. That both words and intentions cannot both be translated is the first quandary, but the translator must sometimes pick one or the other and jump for that. However, at the same time the translator is ethically tasked to not make the speaker look like a fool in front of his or her audience. Thus, the translator often greases the minds of the audience by making the speaker look better by striking more toward what the speaker meant, and could have said given a better understanding of the contextual audience.

These two binds — faithfulness to the speaker’s words on the one hand (regardless of whether we’re talking about sense/word battles), and attentiveness to the relationship between speaker and listeners on the other — directly contrast with any discussion of the possibility of visibility. To translators (and the above example is most visible with simultaneous translation) being visible is a problem. Naomi Seidman writes explicitly about this using her grandfather as an example of being a “double agent.” As a means of getting things done properly, Seidman’s grandfather intentionally altered his translation when telling French gendarmes what he had explained the Yiddish speaking Jewish refugees: to the Jews he said (in Yiddish) that the local Jews would find them and help them that and that they should not be afraid as the French were not Nazis; in response to the gendarmes query of what he had told the refugees, he falsely responded, “I quoted to them the words of a great Frenchman: ‘Every free man has two homelands — his own, and France” (Seidman 2006: 2). He abandoned faithfulness to both the words and their content in the hopes of helpfully interfacing between the speaker and listeners. According to Seidman, the sole reason that her grandfather was able to help the situation (by unfaithfully translating double agent) was because nobody could check him. He gained autonomy through partial invisibility. Invisibility is a key desire of many translators, both so that they can unfaithfully translate words (as with Seidman’s grandfather), but also so that they can faithfully translate problematic ones. An example that is often used in the dangers of translation is Igarashi Hitoshi, the Japanese translator of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, who was murdered following Khomeini’s fatwa against the book and all involved. In a desire to be able to faithfully translate the unwanted message, the translator often wishes to become invisible so as to avoid being shot as the messenger. While far less of a life and death situation, certain freelance translators I have interviewed have elaborated on their happiness when invisible as it allows them greater freedom to not care about the work they produce. Knowing that they are invisible these translators are able to work faster, and earn enough money to spend more time on the ‘better’ jobs where they are given credit for their work (and can put it in their resume/CV). Given these situations, it makes sense that translators do not want always their work to become visible. Issues of trust enable them to continue about their work in a more satisfactory way.

Unfortunately, the translator’s invisibility is only one half of the issue, and putting translators’ desires and well being aside for the moment, the translation’s invisibility is also an issue. Venuti’s (2008) has discussed the discursive invisibility of translation within the United States at length. He has argued that in addition to the above invisibility of the translator there is also a discursive invisibility of the fact of translation within American readers (and by extension, viewers of movies/television and players of games). To Venuti, this is a problem given the United States’ socio-cultural dominance in the late 20th century: the invisibility of translation simply supports an ethnic/cultural chauvinism. For Venuti the answer is to give the translator a partial form of authorship. To acknowledge that the original and translation are (necessarily) different, and to understand the translator as having an equally authorial role. Ironically, one part of Venuti’s claim has come to fruition through the concept of “transcreation.” This is ironic largely because the results of transcreation, as industry tactic, are often far from ethically motivated.

Transcreation is about manipulating a campaign to best sell a product in a local market. The authors of The Little Book of Transcreation compare translation and transcreation by saying, “Translation is about the ability to understand someone else’s language. Transcreation is about the ability to write in your own.” The authors then conclude their small book (about 3 inches tall) by writing, “With literary works, the freer approach of transcreation may not be suitable, out of respect for the original. But where the message is more important than the medium – as in marketing – transcreation ensures that far less is lost along the way. So travel transcreation class, to make sure your message gets there with you.” We can take two important points from transcreation: a) it is not about understanding an other, and b) is is not interested in the original message, but the possibility of making money. So, despite giving authorial authority to the translator (they change the text as they please), both translators and translations remain invisible.

End comments:

translation and (in)visibility are crucially tied

industry secrecy makes this even more prevalent

making money and understanding culture are not the same

References:

- Humphrey, Louise, Amy Somers, James Bradley, and Guy Gilpin. The Little Book of Transcreation. London: Mother Tongue, 2011.

- International Game Developers Association Localization Special Interest Group. Mailing List. September 24, 2012.

- Rollins, Judith. Between Women. Boston: Beacon Press, 1985.

- Seidman, Naomi. Faithful Renderings: Jewish-Christian Difference and the Politics of Translation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Star, Susan Leigh. “This Is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept.” Science, Technology & Human Values 35, no. 5 (2010): 601-17.

- Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer. “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (1989): 387-420.

- Star, Susan Leigh, and Anselm Strauss. “Layers of Silence, Arenas of Voice: The Ecology of Visible and Invisible Work.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 8 (1999): 9-30.

- Suchman, Lucy. “Making Work Visible.” Communications of the ACM 38, no. 9 (1995): 56-64.

- Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2008 [1994].

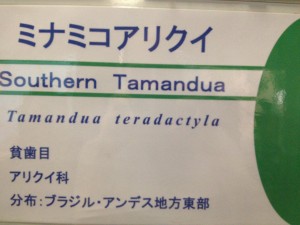

This is everywhere. I just came from the Ueno Zoo, and all standardized signs were written with katakana (despite the animal’s nativity) with English underneath, then the Latin name, and finally in the standard usage with both kanji and hiragana to describe the animal’s eating habits and place of origin. And any argument that katakana might be easier to read for children does not hold, as the nearby signs saying not to feed the animals (arguably what children must read and understand) is written in hiragana, not katakana.

This is everywhere. I just came from the Ueno Zoo, and all standardized signs were written with katakana (despite the animal’s nativity) with English underneath, then the Latin name, and finally in the standard usage with both kanji and hiragana to describe the animal’s eating habits and place of origin. And any argument that katakana might be easier to read for children does not hold, as the nearby signs saying not to feed the animals (arguably what children must read and understand) is written in hiragana, not katakana.  The animal, as an essentially alterier creature, is unknowable/not human, and it is marked as such through katakana. Just like you can never get in the cages, the animals can only be known from afar. Similarly, foreignness is held at bay linguistically through a simultaneous embrace and rejection through the constant utilization, but never full incorporation. Such mixture is a major part of Japan. Not the the most important part, but definitely an important element. So, why then if translation is supposed to bring understanding, does translation never deal with this? And, no, I’m not arguing that Japan is loveydovey, and translations must represent this. Rather, I’m arguing that it is the ethical responsibility of translations not simply to be enjoyable, but to bring understanding of what it is like to consume that text in its place of origin. A text does not travel as some unmarked pleasure, ready for easy consumption, but loaded down with context, necessarily.

The animal, as an essentially alterier creature, is unknowable/not human, and it is marked as such through katakana. Just like you can never get in the cages, the animals can only be known from afar. Similarly, foreignness is held at bay linguistically through a simultaneous embrace and rejection through the constant utilization, but never full incorporation. Such mixture is a major part of Japan. Not the the most important part, but definitely an important element. So, why then if translation is supposed to bring understanding, does translation never deal with this? And, no, I’m not arguing that Japan is loveydovey, and translations must represent this. Rather, I’m arguing that it is the ethical responsibility of translations not simply to be enjoyable, but to bring understanding of what it is like to consume that text in its place of origin. A text does not travel as some unmarked pleasure, ready for easy consumption, but loaded down with context, necessarily.