Introduction: ‘From Translation to Traduction’ to Localization

In this paper, I approach new ways of translating digital media texts— from digital books, to software applications, but particularly my own focus on video games —by mixing traditional translation theory and new media theory. There are similarities between these two fields, but they do not refer to each other. Translation theory rarely looks to films and television, let alone websites, software and games; new media theory fetishizes the ‘new’ and rarely considers that it’s all been done before.[1] I cross the fields because there are mutual benefits to be had by doing so: translation can get new material practices; new media can get more history. I also cross the fields because that is what I see as the work of Communication. Finally, I cross the fields because my own work on video game translation can emerge from their crossing.

While I have already started this paper with confusion (complexity and fusing togetherness), the word ‘translation’ itself has a confused (or perhaps, defused) past. As Antoine Berman notes, it is only in the modern period (post 1500) that the word (renamed ‘traduction’ in romance languages other than English) has taken on its present meaning.[2] Previously, the word (‘translation’) had an unstable meaning because writing itself was never considered the originary act of an author. Instead, all writing, from musing, to marginal notations, to transcriptions, to commentary, to linguistic alteration was considered translation. We are in the process of discursively moving back to the earlier understanding of the word.

The earlier understanding, ‘translation,’ comes from the Latin translatio, which can include the transportation of objects or people between places, transfer of jurisdiction, idea transfer, and linguistic alteration.[3] As Berman stresses, the premodern understanding of translation is as an “anonymous vectorial movement.â€[4] In contrast, the post 1500 term, ‘traduction,’ signifies the “active energy that superintends this transport – precisely because the term etymologically reaches back to ductio and ducere. Traduction is an activity governed by an agent.â€[5] For Modernity and its lauded author this “active movement†through a subjective traducer makes sense, as it distances the iterations by emphasizing a particular hierarchy of original over derivative. However, in a Postmodern culture where global flows and exchanges have moved well away from the author function and the primacy of the work it is helpful to understand the elements of translation that were lost “vectors†in the move to traduction.[6]

For romance languages where ‘translation’ became ‘traduction,’ certain formal and temporal vectors have been lost and taken up by other concepts such as adaptation, repetition, convergence, and intertextuality. While all of these terms have particulars, intertextuality is a useful example due to its link with postmodernity and the move away from grand theories.[7] With postmodern intertextuality there is no singularity of a work. Rather, everything is texts with borrowed themes, images, and sections. Intertextuality follows the formal vector of transformation, which has left translation, but it does not consider power and difference. In the early 21st century United States context, both power and difference are increasingly important and yet elided.

Some vectors were never actually lost in English, as it never switched over to the word traduction. As Berman notes, “English does not ‘traduce,’ it ‘translates,’ that is, it sets into motion the circulation of ‘contents’ which are, by their very nature, translinguistic.â€[8] As the problematically designated world language, English sets itself up as a translinguistic universal, but it does so in opposition to a host of other languages that have switched over to thinking about translation as the necessary and active linguistic alteration to move a text from one place to another. Similarly, while there is an underlying energy that fuels the translational movement of a modern video game over space, there is a simultaneous understanding that nothing the game translator does can change the game as they are not changing the play level. Just like English, play is translinguistic and universal. Current forms of game translation, then, have retained a link to some of the anonymous vectors of translation.

I define translation as the ‘carrying over’ of a text from one context to another, where context can be understood as spatial, formal, or temporal. This broad definition begins to reclaim previously lost vectors, particularly a criticality necessary for the analysis of video games, which are currently exempt as they reside in an area of pure entertainment. This broad definition allows me to consider other forms of textual manipulation including video game localization—the process of translating games for new cultural contexts, which includes linguistic, audio, visual and ludic [play/action] alterations —that has theoretically and practically separated itself from simultaneous interpretation and literary translation. By doing so I wish to force open the definition to include what is already happening, localization, where much of the text is changed for the purpose of a “better†user experience. However, this move allows opens a space for what might happen, such as new forms of translation that use unofficial production to destabilize the meaning of the text by building it up.

I link traditional foci of literary translation theory with some of Jacques Derrida’s theories of deconstruction (particularly of ‘trace,’ ‘living-on,’ and ‘relevance’), and J. David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s concept remediation, in order to reconnect ‘translation’ with its (not quite) lost vectors.[9] I begin with the standard tropes of translation theory — sense and word, source and target, domestication and foreignization — as they do well to show the different possibilities at play with translation. However, disciplinary bound theories are never complete as they ignore extradisciplinary connections. One such connection is remediation. While the concept comes from a literary origin, remediation exists between literary and new media theories; I believe it can help to combine translation in the two areas and help move understandings of translation to new alternatives.

I argue that current practices of translation focus on only one side of the literary theories, thereby turning them into mutually exclusive binaries (sense or word, foreignization or domestication, immediacy or hypermediacy). However, Bolter and Grusin show that remediation is not a binary between hypermediacy and immediacy; rather, remediation utilizes both sides of the equation. Essential to new media is the simultaneous existence of both hypermediacy and immediacy. Current translations espouse only one of these sides, and ignore the benefits of the other. Translation can learn from this simultaneity in new media theory. This paper argues through to a material instantiation of new media translation that takes into consideration both sides of these pairings.

In the second section I show how the dominant practice of translation at present utilizes a domesticating, immediate strategy that overwrites (and thereby renders falsely singular) texts, whether they are literary, filmic, or ludic. In contrast, I argue that a foreignizing, hypermediate strategy that layers texts, which has always existed despite its current lack of presence, can facilitate an alternate, much needed ethics of both translation and cultural interaction. I am not arguing for a simplistic multiculturalism where difference can be subsumed under mere celebration, but for a difficult, abusive, and often painful form of interaction with difference that can reveal the actual ways in which culture functions. As Derrida argues, there is violence and pain that comes with eating the other, but there is also a necessity to eat. One must thus eat [ethically] (bien manger).[10] The same holds for translating.

Tenets of Translation

In the following sections I will review the key principles that have been the focus of translators throughout Western translation history. These examples are primarily from a European/English perspective although I try to use alternative examples where available, applicable and known. I will begin with the impossibility of a perfect translation. Second, I will elaborate on the ways of escaping this core dilemma beginning with the argument between sense-for-sense and word-for-word, and ending with the concept of equivalence. Third, I will review the opposing tendencies of domestication and foreignization as an alternate focus on the author and user instead of equivalence’s focus on the text itself. Finally, I will bring up remediation as concept terms that help bridge literary translation with new media and video game translation and transformation. By linking translation with remediation I can, in the later half of the paper, re-approach Berman’s ‘lost vectors’ of translation, recombine translation and localization, and point out alternate possibilities that are currently unconsidered due to the discursive dominance of fluent translations.

(Im)possibility of Translation

In an almost fetishistic move translation is known for its parts in lieu of its whole. The whole in this case is a holistic notion of perfect translation that completely reproduces a text in a secondary context. As George Steiner notes:

A ‘perfect’ act of translation would be one of total synonymity. It would presume an interpretation so precisely exhaustive as to leave no single unit in the source text —phonetic, grammatical, semantic, contextual — out of complete account, and yet so calibrated as to have added nothing in the way of paraphrase, explication or variant.[11]

Steiner rightly notes such a task is impossible for both an original interpretation and a translational restatement. In fact, the sole example ever given for a perfect translation is the mythical Biblical Septuagint translation where 72 individually cloistered translators made 72 simultaneous translations of the Torah from old Hebrew to Greek over 72 days. As the story goes, their translations were exactly the same indicating divine intervention. However, if one considers the logic of the translation it was the absence of any particular tenet, or focus, that enabled the translation to be considered perfect. God’s weight, on some tenet or another, was imperceptible, so it is the absence of a particular reference that marks the example of perfection. It is the unmarked translation that can be considered perfect, but this does not help with real translations. The practical lesson from the Septuagint is thus that perfect translation is impossible.

The impossibility of a perfect translation has forced all practical translation to focus on certain elements. These elements—sense, rhythm, original meaning, feel, length, and experience—are routinely marked as essential and elevated to primacy. The elements that are considered non-essential are then justifiably negated. One is hard pressed to find some moment, including the present, where this fetishization of certain tenets does not happen.

In contrast to such a partial focus with translation I hope to encourage a use of materiality, which can lead to a fragmented, built translation; imperfect and incomplete, but hopefully leading to a partial picture of what could be. A postmodern translation that is hardly ‘perfect,’ but in contrast to other forms of translation it does not assume justifiable negligibility of unconsidered elements.

I argue that digital new media in particular can enable this form of translation. However, this new method is anything but new, just as new media is anything but new. Rather, it borrows from, and builds upon, both Jacques Derrida and Walter Benjamin’s theorizations of translation. Derrida, in strict opposition to the dream of perfect translation and meaning argues for the slippery sliding of signifiers as a way to point back, but never get back, to an originary moment, text, or meaning. In contrast, Benjamin understands the failures of translation as a necessary part of the dream of messianic return in that they build up to perfection. These two provide theoretical groundwork for what can be made possible by the impossibility of translation.

Derrida’s concept of deconstruction is based in Ferdinand de Saussure’s semiotics taken up to postmodern instability instead of the Formalist dream of an ultimately stable meaning. In the Course in General Linguistics Saussure argues that the linguistic sign is arbitrary in that there is no natural relationship between signifier and signified;[12] it is both variable and invariable in that it changes, but nobody controls the change;[13] it exists as a system (la langue) and individual instances (parole), and this duality makes it both synchronic in its permanence related to langue and diachronic in its relation to parole.[14] As Jonathan Culler argues, what is interesting in Saussure’s linguistics is the relational nature of signs, and therefore how “[l]anguage is a network of traces, with signifiers spilling over into one another.â€[15] Words do not equal each other. Rather, they stand in positions of relationality that depend on time and space.

While Saussure focused on both the synchronic and the diachronic, stable and unstable, system and individual, ways that language exists, the Russian Formalists after him dreamed of a study of stable signs, a Science. Formalists such as Shklovsky and Jakobson (against which Mikhail Bakhtin later wrote) dreamed of an ultimate equality between signified and signifier, of a way that language made Scientific sense. This impetus toward stability and reason drives a great deal of language usage, and it informs practical translation. However, Derrida takes the instability of language, the ‘traces’ that Culler mentions, and runs with it.[16] There is no formal structure to language, there is no deep structure, there is simply the sliding of signifieds on signifiers as words change meaning over time and between utterances. Derrida represents this by the trace, the word under erasure (‘sous rature’). The word is unstable, but this does not indicate that it is free; rather, the word is loaded down with all of the past meanings, the traces of history (whether we recognize those past meanings or not). For Derrida, like with Saussure, meaning can never be pinned down, which means that words are never singular and always slide back along different signifiers; however, for Derrida, this instability means that a translation is twice as meaningful as the original text itself. It is an added sense above; it is an after erasure, a meaning after the original. In light of such polysemy, translation ultimately does something different than simply move a text between form, time and space: it helps the text “live on.â€

In “Des Tours de Babel†Derrida argues that the proper name (Babel, but all names) is the ultimate example of translation’s impossibility. Coming from the Biblical story, Babel is the tower, it is ‘chaos’ (the multiplicity of tongues), but it is also God, the Father.[17] Names remain as they are in translations, they are untranslatable, but this is further the case with God’s name, and the tower itself, both of which cannot be translated/written/completed. Ultimately, Derrida argues that translation is the ‘survie,’ the ‘living on’ and ‘afterlife’ of the original text through the translation, but not the dead, original author whose sole means of immortality is through ever transforming literary texts.[18] As he summarizes in his discussion of a ‘relevant’ [meaningful and raising] translation of Merchant of Venice’s Shylock:

It would thus guarantee the survival of the body of the original… Isn’t that what a translation does? Doesn’t it guarantee these two survivals by losing the flesh during a process of conversion [change]? By elevating the signifier to its meaning or value, all the while preserving the mournful and debt-laden memory of the singular body, the first body, the unique body that the translation thus elevates, preserves, and negates [relève]?[19]

Translation allows a text/body/father, to live on, to survive, but in so doing the original is necessarily changed.

The lesson from Derrida in regards to translation is that it is impossible. This much is obvious. However, impossibility does not mean that it should not be done. Translation is a necessary act despite its flaws: a text would not ‘live on’ without translation, just as we cannot ‘live on’ without eating, consuming, translating the other into sustenance.[20] We can learn two things from Derrida: the first is that deconstruction is about the psychoanalytic working through of the trauma, the historical weight imbedded in the word due to the impossible overload of meanings. The second, the lesson that I take, is that the failure of translation must be flaunted, highlighted. The Derridian methodology (not deconstruction, perse, but the productive theory we may take from deconstruction) is about showing how language and texts have multiple meanings and in fact can never be pinned down to any single meaning. Translation, just like language and original texts, must show this built-in instability. As all language is sliding along unstable signifiers, and all texts float along the backs of others, translation too must show its layeredness, its historicity. However, the instability is not flexibility and freedom, but a painfully historical burden (a ‘haunting,’ even[21]), and Derrida shows this uncomfortable instability by writing with asides, marginal notes and what Philip Lewis has argued as abusive translation.[22] Because this abusive, Derridian style of translation is painful and difficult to read, it is not often considered useful to translation practice, which focuses on clarity, consumption and entertainment.[23] However, the build-up of meaning through layering is a key method to bring together the various modes of translation that I will return to throughout this paper.

Like Derrida, Benjamin argues that perfect translation is impossible, but he does so toward a completely different end. In “The Task of the Translator,†Benjamin argues that the ‘Aufgabe’ [task, give up, failure] of the translator is impossible, but such failures add up to something more.[24] A translation must not reproduce the original, but must be combined with the original to approach something more. His master metaphor is of an amphora, representing language, which has been shattered into innumerable pieces:

[A] translation, instead of resembling the meaning of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original’s mode of signification, thus making both the original and the translation recognizable as fragments of a greater language, just as fragments are part of a vessel.â€[25]

The amphora is language and in order to piece it together individual, failed translations (and the original) must be undertaken piece by piece in order to piece the ‘Reine Sprache’ [pure language] together. Finally, translations are not necessarily possible in any given time; there is a timeliness, or “translatability†that allows or prevents certain translations.[26] For Benjamin, no translation is necessarily possible and no translation does everything, but translations must be undertaken both for Messianic (it facilitates the return to a pure language) and logistic (it enables the spread of ideas and texts) reasons.

Individual translations do not do everything, but as particular translations in particular contexts they give a glimpse of the pure language. From Benjamin I take the notion of seeing something more even if the singular is not perfect, and I take the idea that particular translations are better in particular contexts. Both of these oppose the idea of a singular, perfect translation, which, like Derrida’s insistence of abuse, is little desired by practitioners of popular translation. However, it is something that has great importance in a world where the difference between believing in a perfect translation and understanding the problems of translation can be the difference between fun and boredom, but also between death and life.[27]

While I do not believe in a Messianic return of an Adamic language, I do agree with Benjamin’s insistence on the unequal benefit of different translations. Certain languages at certain times translate better than others due to contextual issues. This is not to say that translation at any given point is fundamentally impossible, but rather that translations are unequal. While Benjamin might hold that this renders useless certain translations at certain times, I believe that it is possible to use the materiality of new media to combine Derrida’s abusive slipperiness of language with Benjamin’s build up of languages to create a more complete translation. Such a new form is where this paper will ultimately conclude.

Word, Sense, and Equivalence(s)

While Benjamin, Derrida, and a large number of other theoreticians of translation confront (and embrace) the impossibility of translation, practitioners of translation routinely deny the impossibility by necessity. Translation must (and does) happen, so instead of a holistic notion of perfection, individual elements are highlighted. Historically, the two primary tenets of translation have been the oppositional mandates of translating word-for-word, and translating sense-for-sense. However, theorists in the 20th century expanded the either/or of word vs. sense to include a host of other correspondences and equivalences. In the following section I will go over these different forms of practical translation, but I will conclude by pointing out that at issue with all of them is that they naturalize a single element, which blocks off the possibilities of any other options.

The oppositional mandate between word and sense has been a major focus in Western translation since the Greeks in part because of the importance of the Bible in Western translatology. The conundrum posed within the oppositional mandate is simply does the translator translate the words in front of him/her [word-for-word], or the meaning of those words as a larger whole [sense-for-sense]? However, because this debate has been contextualized historically within the realm of Bible translations it has never been a simple question between sense and word, but between worldly sense and divine word.[28]

The ‘first’ Bible translation was the previously discussed Septuagint translation from Hebrew to Greek, which was done ‘by the hand of God,’ but manifested through the separate acts of 72 individual translators. In this instance, the translators create what is known thereafter as a perfect translation. The words are God’s words and can neither be altered nor denied. It is the perfect translation as there was unified meaning between original and translation in word and sense. Such claims for perfect word-for-word and sense-for-sense translation are quite problematic, but they go unquestioned until St. Jerome again translates the bible from Greek to Latin. The problem (or so it is claimed) is that he refers back to the old, pre-Septuagint Hebrew version of the Torah, and in so doing denies the primacy of God’s perfectly translated words. How can the Greek version be perfect, with all of the sense of the original in the new words, if Jerome must go back to the Hebrew?

While St. Jerome argues for sense-for-sense translation, he does so in an interesting bind having translated the Septuagint Bible while referring back to the older version and highlighting the importance of particular words. He thus pays very close attention to word-for-word ideals, noting the importance of word order with mysteries, but ultimately argues, “in Scripture one must consider not the words, but the sense.â€[29]

Word-for-word translation schemes never work, as there are never equivalent words. To show how this works I’ll take the word ‘wine’ between English and Japanese: wine is not blood; wine is not saké; saké is definitely not blood. Wine rhymes with dine and whine, but it is also either white or red and can be related to both debauchery and blood, and even metonymically to Christ’s blood. Of course, wine is the fermented liquid from grapes, but also just the general fermentation process itself so that “rice wine†is fermented rice starch, and “plum wine†is fermented plum liquid, but “grape wine†would be considered redundant. On the other side, saké, the Japanese word from which “rice wine†is often translated, stands as a general word for all alcohol, but nihonshu, or Japanese alcohol, which is the more explanative Japanese word for saké, is unused in English. Finally, there is no link between sake and blood in color, rhyme, or any other mode of meaning. If one single word can cause this (and more) trouble it should come as no surprise that a word-for-word translational scheme must fail.

From Jerome through to the modern period there is a fixation upon sense-for-sense translation, and by the time of John Dryden sense-for-sense translation (except when dealing with mysteries of the divine word) is cemented. While metaphrase, word-for-word, is one of Dryden’s three types of translation it is only done in extreme cases. The main debate is between paraphrase, sense-for-sense translation with fidelity to the author, and imitation, which is a type of adaptation that partially betrays the original author.[30] Dryden’s third form of translation, imitation, is the divergence point between adaptation, what I seek to note as a carrying over of form where the translator hints at the style, form or sense of an author, but not the content. Between Dryden and the present this form has completely diverged into adaptation and intertextuality, which are considered entirely separate from translation. This is the final splitting point between translation’s original vectors and traductions’s linguistic and authorial focus in the modern period. Finally, Dryden’s second form of translation, paraphrase, is the most general concept of sense-for-sense translation as it is about what the author said in one language said in another language.

Paraphrase translation has enjoyed the primary role in translation from the time of Dryden to the present, and has only faced significant opposition during the 20th century from semiotics, formalism, and postmodern ideas of language. All three of these provided different oppositions, but all significantly affected the word/sense divide.

While Jakobson is mainly known within translation studies for his three types of translation (intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic), as a formalist he is understandable as one looking at the formal qualities of language, and therefore what happens to those essential elements in the process of translation within and between languages and forms. Moving from a semiotic understanding of language where “the meaning of any linguistic sign is its translation into some further, alternative sign,†Jakobson argues that there is never complete synonymy as “synonymy, as a rule, is not complete equivalence.â€[31] A translation, regardless of word or sense, cannot fully encapsulate the source text. As Jakobson claims, “only creative transposition is possible†where this creative transposition focuses on something, but loses some other specificity.[32] While two possibilities coming from this failure of translation are Derrida and Benjamin, a more common one is to instead focus on creative transposition of one particular element of the text, but ignoring the rest. This is most visible in Nida’s ideas of correspondence with Bible translations, Popovic’s four equivalences in literary translation, and finally the current style of game localization.

Eugene Nida is best known for his principles of correspondence, formal and dynamic (or functional) equivalence, which he has primarily enacted with Bible translations. As a translator closely linked to the American Bible Association most of Nida’s work is also linked to principles of missionary work and the spread of Christianity through rendering the Bible understandable and close to a target audience. His two sides of translational equivalence, formal and dynamic/functional, are quite similar to Dryden’s metaphrase and paraphrase. However, in particular, formal equivalence focuses on fidelity to the source text’s grammar and formal structure. In contrast, dynamic equivalence seeks to make the text more readable to a target audience by adapting it to a target context. Nida’s scalar of equivalence is similar to both the word and sense debate as well as the domestication and foreignization debate, which I will elaborate below, however, that he uses the idea of equivalence in the singular and deliberately notes that one must sacrifice one side or another is important for the current discussion.

In a slightly more expanded sense, Anton PopoviÄ writes of four types of equivalence within a text: Linguistic, Paradigmatic, Stylistic (Translational) and Textual (Syntagmatic).[33] The first, linguistic word, is the goal of replacing a word in the source language with another, equivalent word in the target language; it is different from the word and sense debate in that it simply indicates that the translator must pay attention to the phonetic, morphological and syntactic level of the text, which is to say the words that are written. The following three expand on the idea of equivalence in that a translation may focus on the grammar, the style, or the expressive feeling of the text.

PopoviÄ’s focus is on a very literary understanding of the text. These four methods are for understanding the formal qualities of the written word, and therefore how to translate literary texts. Obviously, these four equivalences do not cover the entire realm of human experience. Other media involve different essential qualities, which have been the focus of those types of translation.

While any medium can offer an example of a different essence, I draw from my own focus on game translation. Game translation highlights experience. Games, as mass produced commodities, are considered interactive entertainment, and the core of the game is the active, fun experience.[34] In light of this gaming essence, the equivalence sought by game translators is the experience of the player in the source culture. As Minako O’Hagan and Carmen Mangiron, two of the few theorists on game translation write:

[T]he skopos of game localization is to produce a target version that keeps the ‘look and feel’ of the original… the feeling of the original ‘gameplay experience’ needs to be preserved in the localized version so that all players share the same enjoyment regardless of their language of choice.â€[35]

Because the optimal experience when playing a game is entertainment, a good game translation is one that entertains and nothing more.

While PopoviÄ believes there is an “invariant core [meaning]â€[36] that remains regardless of any translational variations, one may translate with the goal of rendering equivalent only one of the elements, and in so doing the other three are sacrificed. Such a sacrifice works directly off of the understanding that perfect translation is impossible. Choosing one equivalence over another does not elevate it in importance over the others. However, in the practical integration of translation and reception only one rendering of one equivalence is ever seen, indicating that it is the true equivalence. Because only one type of equivalence is ever seen it is retrospectively elevated to the true equivalence. The equivalence highlighted becomes the essence of the text regardless of it being only one of many and any other types of translation that highlight the other elements of the text are useless. In the case of video games the fetishistic focus on the experience of the player renders invisible and invalid all other levels of the game. As a result, games become pure entertainment and all artistic, political, or cultural levels are ignored.

A text does not have a single essence; it has many different sites of differing importance to different people. The author might be intending to highlight one thing; the reading takes another; one cultural context focuses on one element, but another focuses on another. While the essence of a text spread to innumerable sites (rhyme, look, site, context, etc) equivalence seeks to focus on one and sacrifices the rest. This sacrifice is naturalized, and the equivalent element is constructed (after the fact) as the ultimate/important thing to be translated. As Lawrence Venuti notes regarding Jerome’s Bible translation, “Jerome’s examples from the gospels include renderings of the Old Testament that do not merely express the ‘sense’ but rather fix it by imposing a Christian interpretation.â€[37] Translation does not just move a text from one language, time or place to another, but rather, it imposes particular meanings on that text and through the text on both the source and target cultures. Translational regimes and translations themselves exist within a political world. Translation is inseparable from power.

Domestication and Foreignization

While equivalence flows logically from the debates of sense-for-sense vs. word-for-word it also comes from the other primary concern in translation, which is between domestication and foreignization.

In an attempt to move beyond the debate between paraphrase (sense) and imitation (adaptation),[38] Friedrich Schleiermacher argued that there were two main ways of translating: either the translator makes the text in the style of the foreign original and forces the reader to move toward that source text and context [foreignization, or Source Text orientation (ST)], or the translator relocates the text into the target culture, pushing the text into the local context making it easier for a reader to understand [domestication, or Target Text orientation (TT)].[39] Schleiermacher argued that the debate between sense and word was defunct as both fail bring together the writer and reader. Instead, he contended that the translator needed to decide between foreignization and domestication, as the act of translation was necessarily related not to texts, but to cultures.

Schleiermacher argues that different types of translation are necessary to provoke different reactions in different audiences. Imitation and paraphrase must come first to prepare readers for the higher phases of true translational style: foreignization and domestication. He then argues that writers would be different people were they to write in, or be positioned as if they were writing in, foreign languages as domestication claims to do, and that such a repositioning would take the best elements out of the writers.[40] Thus, his argument ultimately supports foreignizing translation.

Antoine Berman understands Schleiermacher’s call for foreignization as a particular moment where an ethics of translation is visible. This ethics relates to the formation of a German language and culture. To Berman, domestication denies the importance of a mother tongue itself, and foreignization has the possibility that the mother tongue is “broadened, fertilized, transformed by the ‘foreign.’â€[41] However, he also notes there are extreme risks to such nation building:

inauthentic translation [domestication] does not carry any risk for the national language and culture, except that of missing any relation with the foreign. But it only reflects or infinitely repeats the bad relation with the foreign that already exists. Authentic translation [foreignization], on the other hand, obviously carries risks. The confrontation of these risks presupposes a culture that is already confident of itself and of its capacity of assimilation.[42]

The prime assumption here is that Germany exists on the cusp of the ability to incorporate the foreign tongue in order to grow, but more importantly it also exists in a situation of being dominated by the French. In order to negate the French dominance over the German culture and tongue (that is extended through domesticating translations and bilingualism) it becomes necessary to take the dangerous plunge and move toward a foreignizing form of translation.

Texts do not exist outside of contexts, so any choice is necessarily related to political interests. In the case of Germany in the 19th century it was the relationship between Germany trying to develop against a dominant France. As Lawrence Venuti notes about Berman and Schleiermacher, “The ‘foreign’ in foreignizing translation is not a transparent representation of an essence that resides in the foreign text and is valuable in itself, but a strategic construction whose value is contingent on the current situation in the receiving culture.â€[43] In the case of 19th century Germany, Venuti argues that the “Schleiermacher was enlisting his privileged translation practice in a cultural political agenda: an educated elite controls the formation of national culture by refining its language through foreignizing translations.â€[44] Venuti’s argument requires jettisoning the nationally chauvinistic quality of Schleiermacher’s call for foreignization, but maintaining foreignization’s oppositional quality. To Venuti such a foreignization is necessary to oppose the current discursive regime of transparency that is dominant within the 20th and 21st century United States.

Venuti argues that the dominant discourse of translation within the United States is transparency. The translation must read as if it were written in the local language. This is a modern rendition of Schleiermacher’s domesticating translation that has been normalized to the extent that foreignization as a method is not an alternative, or different choice, but an awkward oddity.[45] As his subtitle “A History of Translation†indicates, Venuti lays out a genealogy that shows the rise of fluent translations in Europe between the early modern period and the late 19th century and how during this period the translator’s status dropped. By pointing out the constructed nature of the ‘fluency is good’ discourse, Venuti is trying to argue a move away from such fluency. He does so both to raise the status of the translator in relation to the author and originality, and to problematize the United States and English’s relationship to other countries and languages. As he writes in his conclusion:

A change in contemporary thinking about translation finally requires a change in the practice of reading, reviewing, and teaching translations. Because translation is a double writing, a rewriting of the foreign text according to values in the receiving culture, any translation requires a double reading… Reading a translation as a translation means not just processing its meaning but reflecting on its conditions – formal features like the dialects and registers, styles and discourse in which it is written, but also seemingly external factors like the cultural situation in which it is read but which had a decisive (even if unwitting) influence on the translator’s choices. This reading is historicizing: it draws a distinction between the (foreign) past and the (receiving) present. Evaluating a translation as a translation means assessing it as an intervention into a present situation.[46]

Writing, translating and reading are contextually contingent acts and one must be aware of the contexts from which and to which such texts move. It is key that the discursive regime of domesticating/fluent translation does not allow such historicizing or cultural understanding, as the foreign is simply rendered invisible

The current regime of translation is one in which the translator has become invisible and this has negative effects regarding the translator’s status, but also in regard to couching the United States’ translational imperialism. Venuti argues, “Schleiermacher’s theory anticipates these observations. He was keenly aware that translation strategies are situated in specific cultural formations where discourses are canonized or marginalized, circulating in relations of domination and exclusion.â€[47] Results of this naturalized, extreme form of domestication are transparent cultural ethnocentrism and domination. These are, as Venuti argues, “scandals†of translation.[48] In opposition to these scandals, a foreignizing translational regime can link up to an “ethics of difference†that “deviate[s] from domestic norms to signal the foreignness of the foreign text and create a readership that is more open to linguistic and cultural differences.â€[49] It is Venuti’s argument that acknowledgement and accommodation of difference are sorely lacking with late 20th and early 21st century United States context, thus requiring the switch to foreignizing translation. However, as previously stated, such a foreignizing method is completely opposite the dominant trend of the present.

Venuti argues for a switch to foreignization and away from the domestication that has been naturalized. He argues that “invisibility†refers to both the status of the translator as negated under the writer economically and functionally, and that translations must be presented so fluently, as if they were made in the local language and culture, that the translator is rendered invisible. The invisibility of domestication overlaps in instructive ways with Bolter and Grusin’s concept immediacy, the transparent side of remediation. Ultimately, remediation is a way out of the problematic discursive regime of translation that Venuti locates.

Remediation

In their seminal new media text J. David Bolter and Richard Grusin coined the term remediation in response to what they saw happening with new media at the time, but also how all media had been changing over the twentieth century.[50] For Bolter and Grusin all media is remediated: a medium remediates other media. Web pages have text, icons that tell people to ‘turn to the next page,’ and imbedded movies with standard filmic controls; Microsoft Word has a ‘page’ as it remediates writing on paper. This remediation has two qualities, or sides. The first, immediacy, is where the fact of remediation is cut away, or rendered invisible. The HUD (heads up display) of a game is lessened, removed, or rendered diegetically relevant. From a literary standpoint the content and diegesis is all that matters and the user need not leave this place of immediate access to the text. As Bolter and SIGGRAPH director Diane Gromala write a few years later, “we…have lost our imagination and insist on treating the book as transparent…. We have learned to look through the text rather than at it. We have learned to regard the page as a window, presenting us with the content, the story (if it’s a novel), or the argument (if it’s nonfiction).â€[51] The second, hypermediation, can be seen in TV phenomena such as showing a miniature window in one corner of the screen and in the scrolling information bar on the bottom of the screen, but it is also footnotes, side notes and commentary with books. For Bolter and Grusin remediation is simply something that happens with all media and has happened since writing remediated speech, much to Plato’s chagrin. However, it has interesting links with translation, particularly in how immediacy can link up with Venuti’s fluency, and how hypermediacy can link up with the possibilities of layered translation, which come from Derrida and Benjamin.

Venuti claims that the current regime of domesticating translation within the United States leads toward a fluency that renders invisible both the translator and the fact of translation. According to the majority of American readers who enjoy this type of translation and experience such a goal is admirable. According to Venuti, fluency is quite problematic due to the translational ethics of difference involved. Within the logics of remediation, by rendering the translation invisible the original text is made an immediate fact for the reader even though it is not the original text, but the translated version. This type of immediacy materializes in particular ways with particular media: for books it is in a one to one fluent translational strategy, with film it is dubbing and remaking, and with video games it is localization. While these fluent/immediate strategies are dominant at present there are alternatives.

For Venuti, the opposite of translational fluency is a foreignization that highlights the ethics of difference. As cited above, most important in this is creating a new style of “double reading†that requires the reader read the text as a translation. However, if we take Bolter and Grusin’s oppositional strategy of remediation, hypermediation, we can see alternative methods of highlighting an ethics of difference. Translational hypermediation would entail highlighting the fact of translation; it could be abusive, Derridian translation; it could be Jerome McGann’s hypermedia work; it could be cinematic subtitles and metatitles; it could be game mods.[52] All of these interact with the medium in a way that utilizes its particular form.

Hypermediated translations of new media could easily exist, because of the particularities of digital alterability, but they do not. In the following section I will elaborate the particular way that translation happens materially with books, film and games. Primarily, these current ways are domesticating, fluent and immediate. Then, I will explain how translation could bring out both a type of foreignizing, layered and hypermediate relationship with the text.

Specific Iterations in Media

While the above section has summarized tenets of translation primarily coming from literary studies, the following will elaborate how these different trends intersect with three particular media: books, film and games. These three media are chosen very deliberately. Gaming is my main focus in part because of industry and theoretical denial of its translated nature, and in part due to its ability to lead to new translational possibilities. However, books and film are necessary predecessor forms on the route to games. Books are important as the primary textual form in current Western literary culture. While poetry, newspapers, magazines and other printed forms are also relevant I limit my analysis to the Modern novel both for space issues, and for the novel’s focus on, and obsession with, the author. Secondly, film is important as games have been created in the wake of the 20th century’s cinematic revolution where the language of games comes in part from the language of cinema: cut scenes, 1st person perspective, and increasing obsession with realisticness.[53] While the link between gaming and cinema has been critiqued on the grounds of gaming’s material and experiential differences from cinema, this does not deny its historical and stylistic links despite their unwieldy application in games.

Books, Supplementarity, and Digital Culture

Books in the modern period are singular objects created by singular authors. An author has an idea, struggles to bring this (original) idea to paper, and over time eventually uses his or her singular language to write the work. While books are made at one point in time, there is a belief in their timelessness: they are able to stand up to decades, centuries, and millennia (although such durability is also a test of worth) due to their original language (or rather, despite their original language, as it is translation that allows the text to ‘live on’). There is an essential link between author, nation and language, which is brought out in the book, and readers partake in this art when they read the book.

A translation is something that comes chronologically after the book. It is the result of taking the words and sentences (the content), and changing it into another language in order to facilitate the book’s movement over spatial-linguistic borders. The translation’s hierarchical relationship to the original book is derivative, but its material relationship has changed over time. Whereas translations are a material replacement that comes chronologically after the original, they were at times both simultaneous and supplementary to an original work.

Certain texts needed to be written in certain languages (Latin for religious, philosophic and scientific texts; literary genres in Galican or Arabo-Hebrew, and travel accounts such as Marco Polo’s and Christopher Columbus’ in a hodgepodge), and the idea of deliberately altering a text from one language to another was not high in priority, or even acceptable in some instances.[54] At one point in lieu of translation there was commentary, or Midrash in the case of the Torah. Such commentary was necessarily displayed alongside the original as a supplement. It complicated, but did not replace the original.

This older form of supplementarity can be linked to the current, but uncommon, practice of side-by-side translations where the original resides on one page and the translation on the other. The original and translation face each other to enable comparison. While Biblical and philosophical material is often granted side-by-side translations it is done so due to the importance of both individual words and overall sense, or because the question of just what is important is either undecided or unknowable. In the case of popular (low) cultural novels there is less reason to consider the original and so there is little reason to print the original. Other possible reasons side-by-side translations of important biblical, philosophical, and literary texts still exist, but popular novels are almost never given such a translational method are cost and size. Halving the pages printed should significantly reduce the cost and size of the book. Only important texts, or political and religious ones where price is not an issue, can justify the additional cost of the double pages. And popular, semi-disposable entertainment texts are less entertaining when enormous, bulky tomes. What is a complimentary relation between original and translation becomes a matter of replacing one with the other.

The shift from supplementary translation to replacement translation, where the translation stands on its own as a complete text, happens at the same time within modernity as the rise of translational equivalences. However, as discussed previously, it is impossible to conduct a perfect translation that conveys word, sense and all equivalences, so one element becomes the focus and under that equivalence the translation replaces the original book. In the case of the 20th to 21st century United States this equivalence is roughly what the author would have written had he or she been from the United States and writing in English. Because the industry follows a replacement strategy that supports fluency and immediacy, books can only follow a single equivalence. However, the materiality can support multiple equivalences through a translational supplementarity that supports an ethics of difference and hypermediacy.

Obviously, page-to-page translation, and the works of Derrida are an example of how books can support this form of hypermediated translation.[55] The viewer can be shown the different words that could have been used throughout the translation. While there are many possibilities for a hypermediated translation, there have been few opportunities throughout Western translation history. However, this hypermediated style might be coming back in fashion with the advent of new technologies including the digital book. These digital books also solve cost and size issues that were partial reasons against side-by-side complimentary translations.

While the digital book holds much potential, proprietary design, national based sales of content, and Digital Rights Management (DRM) issues plague current eReaders. They are simply an alternate way to read a book, which one must buy from a massive chain store in one language, and nothing more; they are monolingual devices that bring out the same trend of immediacy that I described above. However, the digital book could be programmed to show a multiplicity of versions, iterations, and translations. It could be programmed to be a truly hypermediating experience if only by linking different translations of a text. I will return to this in the final section of my paper, but a hint at this possibility is in Bible applications. YouVersion’s digital Bible application[56] has 49 translations in 21 languages, and this number increases as new versions are added. The Bible is not in copyright, but it would be possible to use a micropayment system that would allow interested patrons to buy linked versions of different book translations in a similar manner. By integrating the different variations a hypermediated experience would be created.

Film, Dubs, Subs, Remakes and Metatitles

The contentious relationship between immediacy and hypermediacy is highly visible in film translation.[57] On the one hand there is a long history of replacement/transparency with multi language versions (MLV), dubbing and remaking, but on the other hand there is an equally long history of subtitles. While the debate between subtitles and dubbing is really only solvable by referring to local preference, I argue that the rise of remakes of foreign films, especially in the United States, is a sign of the dominance of replacement and immediacy strategies. In the following section I will outline the history of language in film, then how it intersects with remediation, and finally ways that the lesser-used hypermediacy might bring out alternate forms of film translation.

When cinema was first exhibited there was no call for translation. There was no attached sound and there was no dialogue. The original ‘films’ like the Lumière Brothers’ La Sortie des Usines Lumière (1895), which depicts the workers leaving the Lumière factory, and L’Arrivée d’un train á La Ciotat (1896), which shows the train arriving at the station and people beginning to get off, are good examples of the limited structure and general ‘universality’ of the earliest films. Because there were no complicated plots or multiple scenes it was believed at the turn of the 19th century that cinema, like photography, was merely the “reproduc[tion of] external reality.â€[58] At the beginning of the 20th century, cinema was considered outside of language and universal.[59] This understanding was first troubled with the inclusion of intertitles, as they required translation to move the film from one place to another, and from one language to another. However, the rest remained ‘universal.’

The late 1920s brought imbedded sound to cinema, and with it came talkies. These talkies necessitated a new level of translation, and both immediacy and hypermediacy translation styles were available: dubbing and subtitling respectively. Subtitling is both hypermediating and foreignizing. It is hypermediating in that it accentuates the fact of translation by putting the translated dialogue on top of the film. It is foreignizing because of the constant, visible disjoint between the words of the actors and the subtitles at the bottom of the screen.[60] The viewer constantly hears the foreign other, and this brings to the forefront the issue of trusting a translator to have translated properly.

In contrast, dubbing is immediate in that it erases the voices of the visible actors and replaces them with other voices in the target language. However, dubbing is not perfectly domesticating as there is a discrepancy between the bodies on screen and the dialogue. This discrepancy is partially the result of lip-syncing issues, and partially the result of differently signified bodies and voices. One of the tasks of dubbers is to forcefully make the dialogue match the lips by altering the linguistic utterances, often quite significantly.

While dubbing can alter the words and voice coming out of the body it cannot change the bodies themselves. In a realm of racialized nationalism, or as Appadurai writes, when the hyphen between the nation and state is strong,[61] this discrepancy between racially different body and local language is a problem. Because it is assumed that only those with specific bodies speak specific languages such discrepancy is highlighted.[62] Dubbing thus still has a hypermediated quality to it. A further step toward immediacy is changing the body. There have been two different methods used to make films more immediate by changing the bodies. The first was the early 20th century multi and foreign language versions, and the second was the much more long lasting remake.

The understanding of film as universal was initially challenged in the 1929-33 period, which saw the inclusion of multi and foreign language versions. Foreign language versions (FLV) are where the film was recreated after the fact in a different studio, and multi language versions (MLV) are when they were recreated in the same studio on the same set with different actors, but later in the same day.[63] The M/FLV highlights that there were people who understood that culturally specific elements are writ large on the body. Not only was national culture inscribed with language, but with bodies, clothing, and even story. It was believed that replacing the body, remaking the film into both the ‘local’ language and body, the film would be less foreign. This effort reveals the dominant trends of immediacy and domestication. By replacing both the language and body the text is made even more transparent for the audience. However, the M/FLV did not last long largely due to the high costs involved. Then as now there is a high priority given to business and the bottom line, and the cost of making multiple movies simultaneously was not economically justifiable especially when the movie could flop.

While intertitles and the MLV incorporate linguistic and human alteration what they do not consider is the cultural specifics. The content level was not translated or adapted; the stories are not altered. There were incredible numbers of stories adapted and remade again and again, but not because of cultural relativity. This oversight is rectified three decades later with films like Gojira (1954), which was reconceptualized away from the original’s atomic bomb logics. The remake, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), is reshot and reedited in order to feature an American journalist narrator and highlight the monster genre.[64] Following Godzilla, but primarily at the end of the 20th century there was a resurgence of remakes that link with cultural translation.[65]

With remaking not only do the bodies in the film change to locally recognizable ones with their own voices, but the context of the film can be changed from foreign lands to local ones. An example of this is Shall We ダンス (1996), a Japanese movie about a salary man going through a midlife crisis and learning to dance in an anti-dancing Japanese society, which was remade as Shall We Dance? (2004) with Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon and Jennifer Lopez in a Chicago context.

In one of the most important scenes in the original Mai is lectured by a possible new dance partner, Kimoto. He proposes they give a demonstration at a local dance hall (night club), but she refuses to dance with “hosts and hostesses†claiming it isn’t dancing, but cabaret.[66] Mai is obsessed with the foreign, European Blackpool competition and dance floor, which is opposed to the native dance hall with less history and lower culture. Kimoto claims not only that enjoying dance is of primary importance, but that the lowly Japanese dance hall has a history just as important as Blackpool. The opposition of high to low (hierarchical) and native to foreign (spatial) is stressed in this interchange. When Mai finally holds a party that signals the restart of her career it is on the lowly dance hall’s floor, indicating the primacy (or at least equality as she plans on returning to Europe) of the native over the foreign, and it stresses the equality of high and low. In contrast, the remake opposes Miss Mitzi’s relatively unpopular dance studio with the hip Doctor Dance studio and club. The opposition is both temporal and hierarchical: Miss Mitzi is middle aged and teaches various forms of professional dance compared to the scenes in Doctor Dance that are almost all depicted as club/entertainment moments. And when Paulina, Lopez’s adaptation of the Mai character, decides to go study in England (a rather meaningless decision in the context of the remake) her going away party takes place in an unrecognizable locale. In the original, the Japanese spirit and history is implied to be just as important and meaningful as the European one. The film is highly nationalist in its context. The remake works to erase such nationalism by placing the theme of global/universal work and the international family man/nuclear family over that of foreign and native. Such movement complies with a universalization of remaking as domestication. The foreignness of the Japanese original is rendered domestic and immediate with the remake.

A domesticating translation takes the foreign text and moves it into the native context, making the reader’s job easier by forcing the text to speak in a manner the reader is used to. In the Hollywood’s domesticating remake of Shall We Dansu, Japan’s troubled interaction with modernity and globalization are removed. The local socio-political particulars of the original films are erased in the service of “universal†generic narratives that satisfy an American audience that rarely interacts with foreign others. Hollywood’s remake process is a systematic erasure of difference and the foreign other that has been naturalized under the theory of the remake as cinematic translation, which only needs to render equivalent one essential element at the expense of all others.

So far I have discussed the current domesticating and immediate strategies of film translation. Even though I have claimed that subtitling is both foreignizing and hypermediating, it does not use the materiality of the filmic medium to really bring out the possibilities of hypermediation. So far there have been no further creations, but it is not hard to think of a type of “metatitles†that use the capacities of the digital cinematic medium to layer translations on the screen in a hypermediating translational style.

In the last few pages of “For An Abusive Subtitling,†Nornes refers to the fan subtitling of Japanese animation that took place largely between the late 1980s and early 1990s in the United States.[67] With difficult to translate terms the fan subtitlers gave extended definitions that covered the screen with words. The translation effort goes well beyond the standard translation in that it starts with a foreignizing pidgin, but also provides an incredible amount of information that works to bridge the viewer and source. While this abusive subtitling is hypermediating in that it layers the text, it could be extended to use the medium more by layering the text using DVD layers. These layers could move from the main textual layer (the visual film) and the verbal audible signs (dialogue and its subtitles), to the hypermediated translational layers: the visual audible signs (text on screen), the non-verbal audible signs (background noises that need explanation), the non-verbal visual signs (culturally derived, metaphoric camera usage), and any other semiotic layer possible.

Through such a layering commentary of the different signs the screen would quickly fill and overwhelm the viewer as a form of abusive translation, and while there is something admirable in completely disrupting visual pleasure, such disruption would never be taken up by the industry: all film layers must be visible either alternately or simultaneously, and at the control of the viewer. As home video watching is generally at the command of a single user or a small number of viewers the DVD format is a uniquely suited mode to enact metatitles. Due to the increased capacity to store information coming from DVD, Blu-Ray and future technology there is no limit to the possibilities of layering.

A layered translation uses the capacities of current technology by hovering over the text, but just as a translation can never fully encapsulate the original, metatitling would never fully acknowledge every aspect of the original text: it is a failed translation, just as all translation is failure due to being incomplete, but it does so in a foreignizing and hypermediating style that acknowledges its failings, and builds toward some ethical ‘more.’

Games and L10n[68]

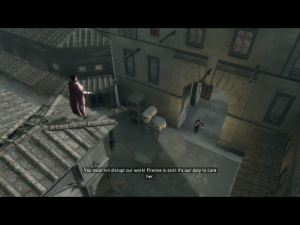

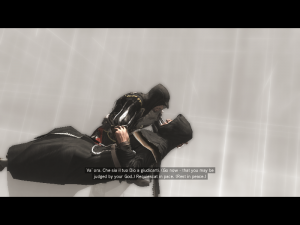

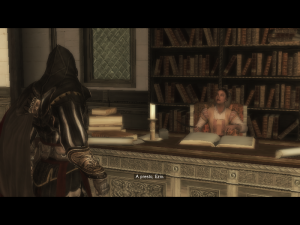

While film translation retained a complex, but present relationship to translation theories and literary translation, the move to new media forms has created a chasm between theories and practice, which has resulted in new methods and industries of translating. Both translation theory and localization practice could benefit from cross-pollination, and that is the heart of my work. The shift to digital software has been accompanied by the rise of a software localization industry (of which gaming localization is an independent but related industry) with its own tools, standards committees and rhetoric. The following section begins by looking at how language intersects with games. I then consider what game localization is and how it succeeds to translate games, but also how it fails to address certain possibilities. One major element is in how localization fails to utilize the possibilities of the digital medium to bring about a hypermediated translation despite the immense amount hypermediation within the medium itself.

Like films, games have an interesting relationship with the idea of universality. The first computer/digital games such as Tennis For Two (1958) and Spacewar (1962), and even early arcade cabinet games like Pong (1972), Space Invaders (1978) and Donkey Kong (1981) were ‘language’ free. In a similar way that the early films were largely visual amazements, games were computer-programming amazements meant to show off the technology.[69] However, the programming was difficult and took up all or most of the available processing power and programming energy. This meant that early games had little processing power or programming time to spare for story. Many held (and still hold) to a universal accessibility and understanding of these games due to the technological and programming limitations coupled with a belief in the universality of play as a social phenomenon. Even now the belief in ludic universality holds despite theorists problematizing that fact in a similar way to how a previous generation of visual culture theorists problematized the universality of vision.[70] For instance, Mary Flanagan has argued, “while the phenomenon of play is universal, the experience of play is intrinsically tied to location and culture.â€[71] While she is largely discussing the spatial politics of games existing in certain spaces, the theory can be expanded to indicate that any game, or instance of play, is tied to a cultural context be it Tennis for Two and the atomic age the weapons research lab in which it was created, Spacewar and masculine science fiction fantasies, Donkey Kong and the origins of the side-scroller as linked to a Japanese aesthetic, or any other game and context. Games are developed, produced and distributed in specific socio-political, temporal and spatial locations and are thus not universal.

However, this believed universality is only now coming into question, and it was completely unquestioned during the 1960s to early 1980s during the 1st and 2nd generations of computer games. There were no ‘words’ in the early computer games, just crude iconic representations. This meant that within the games themselves there was no ‘language’ needing ‘translation.’ What did need translation were the external titles and instructions. Titles were kept or changed to the desire of the producers and distributers. Pakkuman (1980) turned into Pacman instead of Puckman for fear of malicious pranksters changing the P to an F, but other titles were kept as is or were programmed in roman characters. Instructions for arcades and manuals for home consoles needed more extensive translation, but it was a very limited, technical form of translation. The first generation of computer game translation was thus both limited and little different from the roughest of technical translations, neither ‘literary’ nor ‘political.’

The second generation of game translation came about when games utilized greater processing power and storage capabilities to tell extensive stories. These were earlier adventure games like Colossal Cave Adventure (1976) and Zork (1977-80), which told 2nd person adventure narratives, and the more graphical adventure descendents of the 1980s such as Final Fantasy (1987) and King’s Quest (1987). These broke ground in games by normalizing narrative along with play. These also necessitated a new type of game translation that could address more than just the paratextual elements of title and manual.[72] This generation of game translation led to the creation of an industry for game translation.

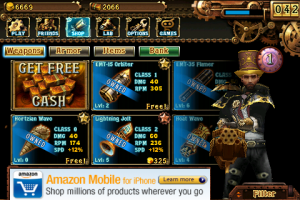

The rise of linguistic material (stories in and surrounding the games) led to an acknowledged need of translation and the beginnings of the localization industry. Originally, the primary method was what is now called partial localization, where certain things were localized, but most others were not. Thus, the manual, title, dialogue, and menus might be translated, but the HUD might remain in the original language due to the difficulty of graphical alterations. The localization industry evolved in the 1990s to match the growing game industry, and localized elements were expanded from menus and manuals to graphics, voices and eventually even story and play elements.

While the current form of game localization is much expanded from early game translation the basics are the same. According to the Localization Industry Standards Association (LISA[73]), “Localization involves taking a product and making it linguistically and culturally appropriate to the target locale (country/region and language) where it will be used and sold.â€[74] Localization is like translation in that it facilitates the movement of software between places, but it is different in that it also allows significant changes in the visual, iconographic and audio registers in addition to the linguistic alteration.

Regardless of how much is translated, game translation involves the replacement of certain strings of code with other strings of code. These strings are usually linguistic: The title The Hyrule Fantasy: Zeruda no densetsu (The Hyrule Fantasy: ゼルダã®ä¼èª¬) becomes ‘The Legend of Zelda,’ and within the game the line “ヒトリデãƒã‚ケンジャ コレヲ サズケヨウ†[it’s dangerous by yourself, receive this] becomes the meme-worthy “It’s dangerous to go alone. Take this!†But alterations are also graphical: a Nazi swastika is changed into a blank armband for games in Germany. The first is a title, the second is a linguistic asset, and the third is a graphical asset. All assets exist as strings of text in the application code, and by altering the programmed code, each can be changed in the effort to move the game from one context to another. The ability to alter assets is an essential quality of new media.

Along with numerical representation, modularity, automation and transcoding, Lev Manovich argues that one of the primary elements of new media is their variability.[75] This idea of variability exists because new media is tied to digital code, which is adaptable, translatable and transmediatable through the alteration of specific strings. Because the strings, especially linguistic strings, are modular there is no specificity to games. With digital games this variability is combined with discourse of play as universally understandable. Because play is considered universal, the trappings of games (form, content and culture) are considered inconsequential, variable, and localized to fit into a target context in a way that does not change the game’s ludic [play] essence. Thus, any level of alteration in the localization process is fully sanctioned in order to provide the equivalent “experience†to the user. [76]

While asset alteration is possible as an essential quality of digital media, it is not simple: a hard coded application can only be changed through painstakingly altering tons of strings all throughout the program. In contrast, an application that calls up assets can change the individual assets into multiple variations and then choose which assets to call. This practice has been enabled in part by the game production industry embracing Internationalization (i18n) as a necessary and regular practice.

Internationalization is the practice of keeping as many game assets as possible untied and unmarked by cultural elements. In his guide to localization Bert Esselink provides an example of an image with a baby covered in blankets and a separate layer of undefined, localizable text.[77] Unlike pre internationalization methods the image and text are not compressed, which makes it possible and easy to switch the text. While the words are changeable the images remain the same, as there is an assumption that a smiling child is universal. Such non-universality of these particular elements is an issue. Games move beyond this by retaining almost all elements as changeable assets whether they are dialogue, images, Nazi armbands, or realistic representations of military flight simulators, but this changeability brings out other problems.[78] It does not address the elements that go assumed as universal that are not, but it also positions internationalization as a lead-in to domestication. Within the ideal of internationalization the practice of internationalization becomes domesticating translation by material and practical necessity. No matter what happens there will be an immediate, replacing, domesticating translation.

If expansive narratives opened games up to larger amounts of translation, there is a conflux of things that led to the third generation of game translation and the eventual rise of the game localization industry. These are the rise of the software localization industry with i18n standards, the understanding of variability and ability to change the games, the creation of CD technology with larger amounts of storage capacity, and finally the use of that storage capacity to enable voice acting to highlight the narratives.

While compact disk technology was created in the 1970s and has been a means of distributing music since the early 1980s, it took until the 1990s for games to be distributed on CDs. Beginning in the early 1990s CD-ROMs were attached to computers and the Playstation gaming device, and games began to be distributed on CDs. This move from floppy disks to CDs greatly expanded the size of games, and with it came the inclusion of both cinematics and digitized voices. One famous early example is Myst (1993). Both cinematics and recorded vocals take a large amount of storage capacity, which the CD provides. However, the CD does not provide enough space to enable multiple languages of vocal dialogue. There was the justified necessity to limit the included languages with a game because of the limited space available. Even when games moved to multiple disks providing multiple audio tracks would have significantly increased the disks required.

The lack of space for multiple languages forced game translators to decide between subtitling the audio and dubbing it over. While this might have led into an equal debate between dubbing and subtitling (like with film translation), the dominance of computer generated (CG) video over live action, full motion video within the games actually led to the naturalized dominance of dubbing and replacing.[79]

As CG requires that voices be added there is little understanding that localization replaces anything. There is no ‘natural’ link between the visible body and the audible voice for CG, so dubbing causes fewer problems in gaming than it does in cinema.[80] However, because of the space issues there was not enough space to provide multiple languages on the single CD, which meant that the majority of games only have one language on them. Certain European regions provide multiple languages by necessity, but this is far from the norm. Even when the storage and distribution method changed from CD to DVD there was little movement toward the inclusion of multiple languages. This lack of included languages is also partially due to the region encoding business practice.

Linguistic multiplicity within games has also been stymied by the practices of video compression for TV and different regions encodings for DVD disks. CDs and DVDs are region encoded in order to protect business interests by opposing ‘piracy,’ defined here as the unsanctioned copy, spread and use of software applications.[81] There are two general eras of this encoding. The first was the separation between NTSC (National Television System Committee) and PAL (Phase Alternate Line). These two methods were linked to the televisions distributed in different regions; the different gaming systems and disks need to operate in the same encoded manner as the televisions. This made it impossible to play European games (PAL) on an American system (NTSC), but it did not necessarily block out Japanese games (NTSC). This initial form of encoding has less to do with piracy protection than it does policing national airwaves. DVDs use a slightly different method in that they are region based between 8 different encodings: in a limited manner they are as follows: US/Canada (1), Europe/Middle East/Japan (2), Southeast Asia (3), Central/South America/Oceania (4), Russia/Africa (5), China (6), undefined (7), international venues such as airports (8). For video games these region encodings work with and against the standard PAL/NTSC distinction so that while Europe and Japan are both region 2 there are differences between the ability to play PAL and NTSC and vice versa. In contrast, while NTSC disks work easily in both Japan and the United States the region encoding limits the ability to play both disks. Both the PAL/NTSC distinction and region encoding have multiple purposes including software piracy prevention, but in terms of translation they legitimize the lack of necessity of translating for multiple regions.