I’ve been thinking about the boundaries of translation and localization lately.

Translation is a specific linguistic alteration, but when it is paired with localization in a way that extends beyond linguistic alterations it re-grasps some of its pre-modern sensibilities. Here I refer to the difference between modern traduction, and premodern translation (. The one is vague movement of a text and the other modern authorial/translatorial alteration of a text from one language to another.

Localization (and particularly video game translation localization) includes graphical and ludic alterations, and even censorship and culturalization alterations (Chandler 2005; Edwards 2006).This change hearkens back to translatio and the pre-modern sensibilities that at one point included commentary on texts (in the margins, or critical exegeses) and adaptations (Dryden 2004 [1680]). What it also leads toward is generic manipulations.

Essentially, what I’ve been thinking about is that the localization from Japanese to English of a game involves (practically) the alteration of coded assets to make it salable within a new linguistic, socio-political and geographical context. Localization helps games move to a new ‘culture.’ However, generic alterations, modding, or reskinning also help games move to new cultures, but in this case the cultures are subcultures, or non-national contexts.

The example that I am working with is Glu Games‘ Gun Bros, which was generically modified into Men vs. Machines. Gun Bros (released on October 28, 2010) and Men vs. Machines (released on April 14, 2011), are almost identical. The assets used for Gun Bros, which was released in 2010, were modified and Men vs. Machines is the result. Glu Games has altered the game from a top down twin thumbs shooter (syntactic genre) within a machismo/sexist aesthetic (semantic genre), to a top down twin thumbs shooter (same syntactic genre) of the steampunk aesthetic (different semantic genre). Furthermore, Glu Games released a third iteration, Star Blitz, on May 26, 2011. The third game also alters the genre, but this time to a science fiction space shooter with ships instead of people.

Title Screen:

Welcome back:

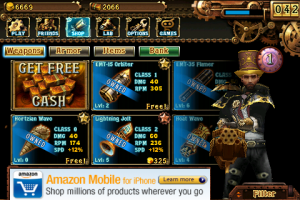

Shopping for new items

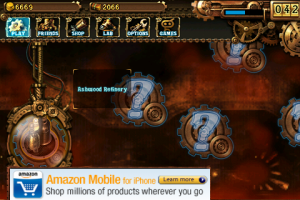

World Select:

Gameplay:

Results of play:

The above shots, Gun Bros on the left and Men vs. Machines on the right, are almost identical. The assets used for Gun Bros, which was released in 2010, were modified and Men vs. Machines is the result. Glu Games has altered the game from a top down twin thumbs shooter (syntactic genre) within a machismo/sexist aesthetic (semantic genre), to a top down twin thumbs shooter (same syntactic genre) of the steampunk aesthetic (different semantic genre).

Generic alteration alone is not particularly strange, as these alterations occur quite often. It is essentially what makes a syntactic genre (the alteration of semantic elements to fit different groups of people). First person shooters in westerns, space, comic books, modern war, old war, etc are all examples of this standard generic manipulation. What is interesting, is that the alterations were done by the one company, and that the way the game plays is identical. Usually the requirement of using an engine is that it must be changed somewhat, or perhaps that is simply what happens to make it a meaningful game to the gaming populace. Ironically, the response of outrage on the Glu forums toward Men vs. Machines from players who are angered that the time they spent in Gun Bros is for naught as the company will switch to updating the Men vs. Machines is widespread.

What is interesting is that the limited alterations raise the core gameplay to an essential level. Because the only thing that changes are the assets that helped relocate the engine within a new, steampunk subculture, the process of altering Gun Bros to Men vs. Machines and then to Star Blitz is the same process as localizing a game.

Where I am now in my thinking can be summed up with the following thoughts: according to LISA, localization is the process that renders appropriate a game for a new cultural context, but that makes adaptation and reskinning the exact same process and a form of localization. If the above is true, then what is the culture to which localization companies seek to render games accessible? Are they as malleable and perfunctorily determined as generic alterations? Are socio-political realities less important than target market desires (which have themselves been created by the marketeers)?

Is it not that the culture to which localization seeks to render games accessible itself created by the process of localization?

References:

- Berman, Antoine. “From Translation to Traduction.” Unpublished translation by Richard Sieburth. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, ReÌdaction volume 1, number 1, 1988: pp. 23-40.

- Chandler, Heather Maxwell. The Game Localization Handbook. Hingham: Charles River Media, 2005

- Dryden, John. “From the Preface to Ovid’s Epistles.” In The Translation Studies Reader, edited by Lawrence Venuti. New York: Routledge, 2004 [1680].

- Edwards, Kate. “Fun Vs. Offensive: Balancing the ‘Cultural Edge’ of Content for Global Games.” In Game Developer’s Conference: What’s Next. San Jose, CA, 2006.