Assassin’s Creed 2 (AC2) is a curious monster. I’m sure the first in the franchise was even stranger due to its Oriental(ist) focus, but I haven’t had the chance to play it (although El Nasr et al. 2008 give an interesting take on it). As such, I’ll keep my comments primarily to the second title in the franchise, which focuses on late 15th Century Italy.

AC2 takes place in the present where the player embodies a character, Desmond, who was previously held prisoner by the Templars (an organization trying to take over the world), but is freed in the opening scene by Lucy, and now works alongside the Assassins (who oppose the Templars and supposedly have throughout history). The cities in which this all takes place are not named overtly, but are within Italy according to fan delvers. Regardless of the specifics, a global north location is assumed due to the general skin color if nothing else. However, the majority of play takes place in a VR set up called the Animus 2.0 where Desmond embodies the Italian Ezio Auditore de Firenze, who encounters dozens of historical personages in his journey for familial vengeance.

You (the player) embody Desmond (a roamer from an unknown place called “The Farm”) who embodies Ezio (an Italian from Florence) as well as Altaïr Ibn-La’Ahad (who is never given a more exact place of origin other than “The Middle East”). The nationalities are near tripled in the game between Desmond, Ezio and Altaïr, and the locales are multilple between the player’s own locale, 21st century Desmond and 15th century Ezio’s locales in various places in Italy (particularly Florence, Venice, and Rome), and 12th century Altaïr’s locale in various places in the now Syria and Israel area (including Masyaf, Acre, Jerusalem and Damascus). Suffice to say, there is no single locale within the game.

While there is a multiplicity of locales within the game, there is a limitation of localizations. When I started up the application for the first time I registered for a US/English account (and this may have created limitations), and upon launch the game’s graphical user interface (GUI) was English. Again, I will need to check alternate possibilities of switching the basic interface language, but for now I wish to discuss the option that remained despite the original determination. Within the option menu I am given the option of English and Italian spoken dialogue. Choosing one or the other makes all of the spoken dialogue in that language, but the GUI remains in English.

While this seems a simple audio switch so far, there is a crucial difference between the English and Italian language options. The Itlaian makes everything in Italian, but the English actually plays between English and Italian languages: certain elements of the characters’ dialogue remains in Italian, and are given a parenthetical English translation in the subtitles after the standard subtitles. Two examples are below:

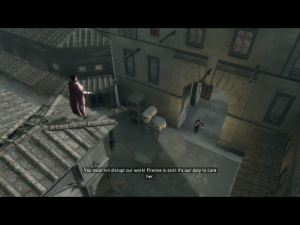

The above image has the standard English. The characters words are given subtitles for both ease of understanding and to aid the Deaf player community. This is standard dialogue between the characters and happens often during cutscenes and other interactions.

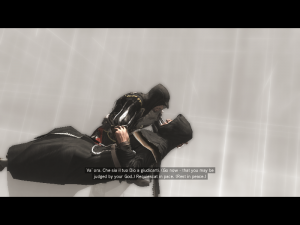

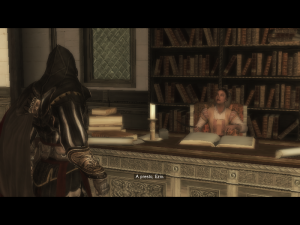

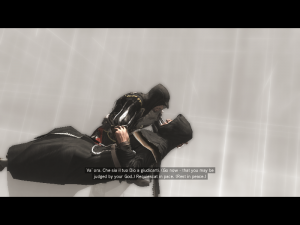

In contrast, the second image shows Italian, Latin and translated English. In the seecne the player has assassinated a main antagonist character and there is a moment between them (the lack of female targets and main characters encourages a homosocial reading by the by). They converse, and then Ezio gives the target last rites as the target dies. The last rites are always in Italian with the Latin “requiescat in pace” at the end; the foreign enunciation remains foreign. Similarly, curses like ‘bastardi,’ and salutations like ‘a presto’ and ‘salute,’ and other colorful terms are often kept in Italian (shown below).

The English maintains a duality of language that forces the player to engage with a certain (albeit limited) foreign experience. This duality is erased within the Italian audio track as the spoken oscillation between English and Italian is removed and replaced with a constant Italian (granted, this Italian makes sense diegetically, but then what happened with the Arabic of the first title?). As a globalized narrative between Assassins and Templars the story necessitates mixture, and as it was made by Montreal based Ubisoft linguistic mixture is not surprising due to the Quebec French and Canadian English situation. However, the question becomes what happens to it as it travels to other languages and locales? Is the linguistic mixture removed within the other localizations? A quick search on YouTube reveals that the Spanish localization uses a variation of “pujar” in Spanish in the first 10 minute segment where there is a short scene of Ezio being born. The nurse says “spingi” (push) in the North American English version that I played. The mixture has been simplified.

The story is about global machinations and mixture, and one of the ways this is made apparent to the player is through the linguistic mixture. Sadly, this mixture disappears with localization. Is the task of localization to maintain a look and feel including politics and difference, or is it limited to entertainment at any cost? When a text is not limited to a single locale can a localization reduce it to a single locale?

References:

- El Nasr, Magy, Maha Al-Saati, Simon Niedenthal, and David Milam. “Assassin’s Creed: A Multi-Cultural Read.” Loading 2, no. 3 (2008).

- Ubisoft Montreal. Assassin’s Creed II [Macintosh]. Ubisoft.